I just finished reading Johnny Cash: The Life by Robert Hilbum and I must say I hated reaching the book’s end, not just because it ends with Cash’s death but because it was such a terrific read. Hilburn is a wonderful writer (music critic and editor for the Los Angeles Times for over 30 years) and he really knows how to tell a story. From what I understand, this book is the definitive biography of Cash (over 600 pages long) and it is brutally honest, well-researched and intimately detailed. It’s not a celebrity tell-all book that makes you feel like you need a shower after reading it, however. Hilburn wrote it with the full cooperation of Cash’s children as well as the Man in Black himself who told the author that “he wanted people to know his entire story—especially the dark, guilt-ridden, hopeless moments—because he believed in redemption and he wanted others to realize that they too could be redeemed regardless how badly they had stumbled.”

I just finished reading Johnny Cash: The Life by Robert Hilbum and I must say I hated reaching the book’s end, not just because it ends with Cash’s death but because it was such a terrific read. Hilburn is a wonderful writer (music critic and editor for the Los Angeles Times for over 30 years) and he really knows how to tell a story. From what I understand, this book is the definitive biography of Cash (over 600 pages long) and it is brutally honest, well-researched and intimately detailed. It’s not a celebrity tell-all book that makes you feel like you need a shower after reading it, however. Hilburn wrote it with the full cooperation of Cash’s children as well as the Man in Black himself who told the author that “he wanted people to know his entire story—especially the dark, guilt-ridden, hopeless moments—because he believed in redemption and he wanted others to realize that they too could be redeemed regardless how badly they had stumbled.”

Mr. Hilburn, himself a secular journalist, weaves Cash’s faith in Christ—inconsistent and contradictory as it was—into the storyline throughout the book. It begins with a picture of young J.R. (he didn’t become “Johnny” until after he started making records) attending church with his family “every Sunday morning, Sunday evening and Wednesday night. Unlike other kids who complained about having to go to church, he looked forward to the music, the sermons and the sense of community.” Hilburn writes that although Cash’s pledge of fidelity in “I Walk the Line” (“Because you’re mine … I walk the line”) was undeniably inspired by his love for his first wife, Vivian (whom he would eventually leave for June Carter), he adds that Cash often spoke of the song as an expression of his allegiance to Christ as well. In fact, Cash called the song “his first gospel hit.” I’ve listened to that song hundreds of times and never made that connection. The book is full of interesting revelations like that.

Johnny Cash has become much better known for his dark side, however—his addictions, his moral failures, his frequent run-ins with the law, and his famous “one-finger salute” photo that went viral after it was featured on a full-page ad in Billboard magazine. According to Hilburn, the photo was taken at Cash’s 1969 concert at San Quentin prison. Apparently, Cash was fed up with the TV crew following him around and decided to send them a little message. The subsequent photo of a snarling Cash flashing his middle finger at the camera was acquired years later by Cash’s record producer Rick Rubin who decided to use it on the Billboard ad in 1998 after Cash’s album “Unchained” won the Grammy Award for Best Country Album. The caption read “American Recordings and Johnny Cash would like to acknowledge the Nashville music establishment and country radio for your support.” (The joke, of course, was that country radio and the Nashville music establishment snubbed the album altogether.) “Cash was uneasy about the ad,” writes Hilburn, “so he called Billy Graham to ask for advice.” Graham’s response? According to Cash, “He didn’t tell me what to do or not to do, just that he wouldn’t judge me either way. After my talk with him, I prayed about it and called Rick back. I gave him the go-ahead.”

I have to say that my opinion of Billy Graham went up after I read that story.

One reason I wanted to read this book is because I have had a couple of personal encounters with Johnny Cash and actually got to work with him when I was in the group Brush Arbor. We played a couple of concerts with Cash in 1973 and we also appeared on a TV special that he did for NBC. I must admit that I checked the table of contents of Hilburn’s book to see if by any chance we got a mention. We didn’t.

We didn’t deserve one of course. That TV show which aired in January 1974 wasn’t a significant part of Cash’s legacy, but it certainly was a highlight of Brush Arbor’s career. We flew from San Diego to New York for the taping of the show which was done at NBC Studios in Rockefeller Center. In a classic case of being too self preoccupied to pay much attention to what was going on around me, I’m sure I spent most of the time in our dressing room practicing banjo rolls rather than soaking in the part of history I was getting to witness up close and personal. Besides Cash and his ensemble (the Tennessee Three, the Statler Brothers, June Carter, The Carter Family, Mother Maybelle Carter, his daughters Rosanne and Rosie, etc.), Bill Monroe was on the show as was Tanya Tucker, Larry Gatlin and Carl Perkins. I can’t tell you how many times I have wished I knew then what I know now. And I also wish I my camera hadn’t been stolen on that trip. I left it in our dressing room while we were taping the show and when I got back, it was gone. So I have no pictures of our time in New York City with Johnny Cash.

But I have some good memories, like the night we went out to dinner with Cash and his family at a famous Italian Restaurant in New York called Mama Leone’s. There were about 15 of us as I recall at the table: Cash and his family, Larry Gatlin and us. After we ordered our meal, I got up to use the restroom. At the back of the restaurant where the restrooms were located, one of the waiters asked me (in a strong Italian accent), “Excuse-a me. Is-a that-a Johnny Carson at your table?” I thought that was hilarious and when I got back to the table I remember Cash got a kick out of it too.

My camera may have been stolen, but thanks to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, I do have video of the performance we did on the that TV Show:

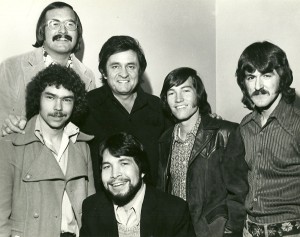

And here’s a photo of us with Cash that was taken by our manager Dan McKinnon. Speaking of one finger salutes, it appears that I (yes, that’s me in the upper left hand corner) was sending an unintentional message of my own.

Back to the book. One aspect of Cash’s life that resonated strongly with me throughout the book was Cash’s determination to keep going, his perseverance. He was strongly committed to his music, his family and his faith and he never gave up on any of them even though he failed miserably and made disastrous personal and professional decisions. He never gave up on his musical career even after it had deteriorated to the point that he was in the mid 1990’s performing in Branson to half-empty showrooms of disinterested blue-haired tourists. I remember seeing Johnny Cash around that same time with a bewildered look on his face standing in a small exhibit hall table at the Christian Booksellers Convention, hawking Bibles for Thomas Nelson. How the mighty have fallen, I thought at the time. But Cash kept on going. Late in life, he finally kicked his pill habit and his sagging career was ultimately revived by rap producer Rick Rubin, the man responsible for some of Cash’s best work, including “Hurt,” the haunting song (and video) that introduced Cash to a whole new generation of listeners. Suddenly he became an international star again.

On a side note, I think it would be wonderful if everyone had a Rick Rubin in his or her life—someone younger and smarter who could bring the best out in us when we get old and stuck.

Rejuvenated as he was, he continued to write songs and record through heart surgeries, neurological problems, a damaged jaw and failing eyesight. He even continued working after his beloved wife June Carter passed away in May 2003. He died four months later at the age of 71. By then, according to one estimate, doctors had him on some 30 medications.

His son, John Carter, later said: “I believe the thing about Dad that people find so easy to relate to is that he was willing to expose his most cumbersome burdens, his most consuming darknesses. He wasn’t afraid to go through the fire and say: ‘I fell down. I’ve made mistakes. I’m weak. I hurt.’ But in doing so, he gained some sort of defining strength. Every moment of darkness enabled him to better see the light.”