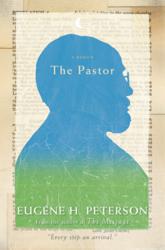

I recently read Eugene Peterson’s memoir, a book simply titled Pastor. Peterson is of course best known for The Message, his wonderful translation of the Bible. But before he was a famous author, he was a not-so-famous pastor of a small suburban church in Maryland.

I recently read Eugene Peterson’s memoir, a book simply titled Pastor. Peterson is of course best known for The Message, his wonderful translation of the Bible. But before he was a famous author, he was a not-so-famous pastor of a small suburban church in Maryland.

For the past year or so I have also been a pastor—not a senior pastor, but a pastor nonetheless. Even though I have served alongside pastors and youth pastors for almost 50 years, I have never actually been a pastor before. In some ways I feel like I’m starting over again in ministry, learning a new vocation that requires new skills and new ways of working with people. I’ve got a long way to go. I thought I would read Peterson’s book to learn more about what it means to be a pastor.

Peterson is a good one to learn from. The book is autobiographical in nature, and it’s a good read. His story is told honestly and with humility. There are also points in the book when Peterson adds some wonderful commentary on ministry, theology and the state of the modern church. For example, when he became a pastor, he resolved to focus on just two things: worship and community. Of these, he writes, “The religious culture of America that I was surrounded with dismayed me on both counts. Worship had been degraded into entertainment. And community had been depersonalized into programs.â€

“By the time I arrived on the scene as a pastor,†he continues, “the American church had reinterpreted the worship of God as an activity for religious consumers. Entertainment, cheerleading, and manipulation were conspicuous in high places. American worship was conceived as a public relations campaign for Jesus and the angels. Worship had been cheapened into a commodity marketed by using tried-and-true advertising techniques. If so-called worshippers didn’t ‘get anything out of it,’ there had been no worship worth coming back for. Instead of calling people to worship God, pastors all over the country were inviting people to ‘have a worship experience.’ Worship was evaluated on the ‘consumer satisfaction scale’ of one to ten.â€

And he writes this on community:

“Church in America was mostly understood by Christians and their pastors in terms of its function—what it did: build buildings, become ‘successful,’ change the neighborhood, launch mission projects, and create programs that would organize and motivate people to do these things. Programs, mostly programs. Programs had developed into the dominant methodology of ‘doing church.’ Far more attention was given to organizing and giving leadership to programs than anything else. But there is a problem here: a program is an abstraction and inherently impersonal. A program defines people in terms of what they do, not who they are. The more program, the less person. … I wanted to develop a congregation in which relationships were primary, a household of hospitality. A community in which men and women would be known primarily by name, not by function. I knew this wouldn’t be easy, and it wasn’t.â€

There’s a lot to learn in this book about how to be a pastor. Peterson served at Christ Our King Presbyterian Church for 30 years, not a big church by today’s standards, but one where lives were transformed and disciples were made. I think I would have loved being a member there.